A Dead Man’s Guide to Flag-Waving

As the 13th state established in the Union, Rhode Island offers history as readily as valets offer to park your car. Most historic sites however, don’t involve a tip or the threat of dented fenders and cracked headlights. This is a good thing. The chance of learning and in a sense, experiencing the history around you can lead to certain knowledge and an appreciation for what events have occurred to help form your current surroundings. The scholar-approved site Wikipedia, lists East Providence as proud owner of at least twenty-one historical sites. Not bad for the fifth largest city in the country’s smallest state. One of the listed sites is the Ancient Little Neck Cemetery. The designation of “Ancient” may be a little overzealous on the part of whoever named the cemetery, but people have been buried there for quite some time. The earliest settlers buried there were of the first Europeans to take up permanent residence in Uncle Sam’s neighborhood; I’m talking pilgrims. Bodies have been set here for decomposition since as early as 1662.

Ancient Little Neck Cemetery is nestled in a wooded and undulating area, tucked in against the shores of Bullock Cove. Oak trees and pines are scattered in dense clusters throughout Little Neck as they jut up from atop hills and peek up from dells of the sloped land. The foliage offers seasonal shelter to the headstones and grave markers. Their acorns and needles stud the ground with soft orange-brown, old embers faded atop the green mossy land, littered amongst the weather-beaten gray gravestones. Where Narragansett Bay meets land at the southern end of East Providence, it forms Bullocks Cove, and the cove wraps around three sides of the cemetery, forming a peninsula. Narragansett Bay was the life source for most in the area at the time the cemetery came into use. Shellfish populations came to dwindle as they were found to be a viable resource for food. It seems eerily fitting for those same waters to wash up against the shores of burial in the same pendulous rhythm in which they drew food and sustenance to the cove’s edge.

The cemetery itself isn’t very big, only 12.3 acres. Though, there has undoubtedly been landscaping and grooming done, it seems more like the maintaining of land as opposed to its alteration. The area emits a rogue and feral atmosphere; it’s hard to imagine it has changed much from its origins in 1655. Little Neck looks untamed and truly rural, as if the only human presence were the deceased. This is an unfortunate observation as it lends itself to the thought that perhaps the only way a human won’t destructively interact with a natural environment is if they’re already dead. It’s a morbid tradeoff, the decomposition of a body instead of the demolition of woodland. It’s unfortunate that this quality of unspoiled land seems to be anachronistic and unfamiliar, I find myself wondering why respect for the dead is a singular reason for the preservation of land, what of respect for the living? Why be bent on notions of preservation for the sake of the past, but feed the future’s environment to the proverbial wood chipper? I suppose I should just be happy to be able contemplate the treatment of life amongst the dead.

The edges of the cemetery are its lowest point, especially its eastern edge. The land slowly rises up to the center, where most of its graves are located, it’s highest point holds up the oldest of the graves. Perhaps community and family members had a logic of altitude in the geography of burial plots for loved ones, the higher up the closer to God and the shorter the ascent to heaven. The physical land offering up the human spirit to God.

From the tops of the hills the waters of Bullock’s Cove can be seen. These are the waters fished by the early settlers, as well as the Wampanoag American Indians who first culled the waters and left the earliest imprints on the land, well before those European Settlers even knew the land existed and realized it would be a nice area to settle down in and slowly destroy through urbanization. The Wampanoag’s were the original settlers on the land where the cemetery now sits, and they have an even more distinct connection to the cemetery.

The first person buried there was John Brown, Jr. The son of, (drum roll please), John Brown Sr.. The elder John Brown was the orchestrator of the deal with the Wampanoag Indians that established the land as being owned by Brown and the village of Rehoboth, the American Indians relinquished their land to the settlers with this deal, signed in 1645, and Wannamoisett became Rehoboth.

Other famous resident of Little Neck are Elizabeth Tilley Howland, a passenger on the Mayflower and original settler of the Plymouth, as well as Thomas Willet, who became first Governor of New York in 1665. In 1913 Willet had an interesting memorial placed at Little Neck in his honor. It is a rock. Well, not really a rock, more like a boulder. A plaque adorning the bottom of the boulder notes that it weighs 27, 500 lbs and that it took one boat, sixteen horses, and twenty men to get it to its, ahem, final resting spot. The large rock seems big enough for a statue to be carved out of and the fact that it was left in its original boulder form made me wonder how great a man Willet really was. Maybe Willet had crossed the sculptor at some point and upon realizing the work he was undertaking, the sculptor said, “to hell with his legacy” and left the boulder as is, forgoing the plans for an eloquent statue of the Guv’na. This is only scholarly speculation though.

One of the plots I found myself most interested in was a family plot. It was set on that “ancient” peak, sectioned off from the public by speckled black iron rods set on coarse stone posts, about waist high, placed there to deter eager tourists from touching the fragile and flaking slate headstones but not interfering with the observation or study of the stones themselves. The surname of the family buried was Medbery and the plot held six pairs of head and footstones. The footstones were another interesting feature of the aged graveyard. They marked where the coffins started and ended, the headstones were significantly shorter than the headstones, short enough that longer tufts of grass reached above them. There were no markings or engravings on the stones, they weren’t shaped evenly or sanded down to a smooth finish, rather, they were jagged, toothed slabs of stone, slightly curved in a misshapen and decrepit mimic of a headstone. Looking down from above, the heights signified by the placement of the stone sets seemed as if the Medbery’s were an extremely short family. To test it out, I lay next to the outermost grave, belonging to Hezekiah Medbury (this name change is not accidental), and it was almost a perfect match. Lying there, looking to my right at the grave stones, myself against the ground in a burial position, was strange and eerie, I was half expectant of arms grabbing me and dragging me to hell like some campy horror movie and half amazed that the ground I was on also housed what remained of person’s that lived through the Civil War. Not just the Civil War, but also the burial spot of fifteen soldiers who fought the Revolutionary War.

Amongst the parents, Hezekiah and Deborah, whose names were Medbury, were four of their children, whose surname had been changed to Medbery. Supposition on that is all I have, perhaps it was a change between the name the family had in England and the name or new identity desired in America. The thing that drew me to study these graves was the dates of death of the four children, all young, the eldest dying at the age of 10, and all passing on within the same four day span between February 26th and March 1st of 1833. The youngest child died at 1 year, 5 months, and 5 days old. The exact age of death, down to the day, was another feature of the older graves, one not seen today, or at least rarely seen. I wondered to myself what must have been the cause of death for all of these young children, surely some tragedy had struck, was it fire? Accident? Most likely it was disease or infection. In 1833 a common epidemic was Cholera and that seemed to be the most likely case. Unfortunately my research fell short and I couldn’t find out for sure the cause of death for the children, nor could any other information be found that would allow some insight into the kind of life the Medbery’s led. The only information that lent itself to any sort of understanding of their life was a small tidbit found concerning the father, Hezekiah, who was reported to have been a dedicated member of the local church, and held the denomination of Deacon. The graves of the Medbery’s were faded and worn. Their lengthy biblical passages mostly illegible, inscriptions reduced to slight imprints, smudged into the stone like ink trailing on wet paper.

Ancient Little Neck Cemetery isn’t an out of use cemetery. Though it’s most likely that the cemetery’s plots are full, there are newer graves, plots requested years earlier or family reserved plots; there are graves from as recent as February 2009. That grave may have been the creepiest to observe, as the new grass hadn’t yet grown, dirt and loose gravel still outlined the space where the hole had been dug. If it had been a windy day I’m sure dust from the plot would have been swirling above it in a mimic of paranormal activity. Accidentally stepping on the fresh grave I left an imprint of my shoe in the dirt but quickly brushed the Nike swoosh away as to avoid any accusations of blasphemy or disrespect for the dead. I also brushed the underside of my shoes off to avoid having to walk around with grave dirt on my sneakers all day.

After returning home from my cemetery excursions I thought I had seen all I needed to see in the graveyard. But through talking with my mom I found out that my great grandfather and great grandmother were buried there. I hadn’t had the chance to meet my great grandmother, she passed away in 1955, but there was an old yellowed Polaroid picture of myself as a young boy, a very young boy, being held by my great grandfather on my grandparent’s couch, he was cradling me. I always felt a connection to him through this picture, there was a love visible there, something that always caused me to think of him warmly, kindly, Ozzie, he was great-grandfather and he was buried here along with these historic figures. He was part of a distinct history himself, a veteran of the First World War.

My parents couldn’t recall where he was buried so it gave me the opportunity to speak to my grandfather, a native Rhode Islander now removed to Florida. Though having moved to Florida over ten years ago he was able to recall exactly where his father was buried, a steel trap memory, teeth set firmly into detail and specificity. With clarity and explicit acuteness he directed me to where the graves stood. They were set in the northeast corner, further away from the older graves and in flatter, grassy area. A great oak stood imposing to the west. It’s height wasn’t its greatest feature but rather the way the branches ran from the trunk, dispersing at several angles and looming across the graveyard as if the tree intended to stir the waters of the cove at the southern end and draw life from it as the fisherman had before. Clovers surrounded the grave of my great-grandfather, Osmond Harrington, who passed away in 1989, two years after I had been born. My dad recalled bagpipes being played at his funeral and I thought perhaps this is why the clovers had been called to life here, birthed from the shrill melodies played by the pipers, music said to be an aid for plant growth. Clovers in my mind were always a sentiment of Irish lore, four-leafed bearer of luck. The air of bagpipes in my mind is always pushed from Irish lungs, it made sense to me.

The sense of history I gathered from visiting Ancient Little Neck Cemetery stuck with me long after I left. It imposed a new view on me. The way I had first approached the preservation of this land, the unchanged and in turn undiminished quality of it, was originally cause for me to view the present day disregard for natural landscapes in a negative light. The scope of history held by this cemetery caused me to change my view. Little Neck contains a history which spans events that occupy whole sections of social studies and history books, events that helped shape and construct our country’s foundations and gave the insight necessary to write documents that our country now holds itself up against as a barometer of values, a history looked upon both in stoic reverence and patriotic ardor, eye witnesses of events all buried beneath the ground on which I had stood, accounts and testimonies buried with them, only to be told through the drawl of history teachers and sequenced in chapters of books, laid out with a known end, story book accounts of the mettle that brought this country through divisive times like the ones of today, where any sense of stability is held in shallow pockets, vulnerable to becoming jarred from them and lost if another bump is hit. The preservation of the cemetery became a source of pride for me; I looked at it as strength, an endurance and spirit that hadn’t been defeated. I am far from nationalistic or patriotic in the sense it has been used recently. Patriotism recently becoming a term perverted and used as a tool for political chastising and not as a source of pride and community, but this cemetery gave me a sense of pride for my country, more accurately, my countrymen. Oddly enough it was a burial ground that gave me this pride. It wasn't a pride for country or state, but a pride in the ability for the perseverance of people. The fact that it still stood unchanged after all these years was in my eyes, a testament to fortitude and strength, represented by the graves of those who had endured and took part in the shaping of this country.

Thursday, June 18, 2009

Monday, June 1, 2009

VIA PREFIXMAG.COM.......

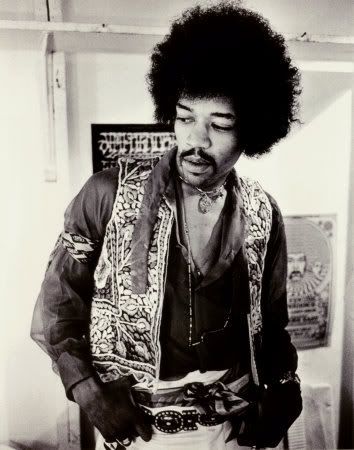

The Jimi Hendrix Experience: Roadie Reveals Hendrix Was Murdered

"James "Tappy" Wright is trying to shill a few copies of his book Rock Roadie by letting loose with one of the book's most choice tidbits off gossip: Michael Jeffrey, Hendrix's manager, made a drunken confession of murder approximately a year after the rock star's death. The idea behind the dastardly deed was a basic insurance scam. By staging Hendrix's "accidental" death with an overdose of barbituates and red wine, Jeffrey was able to collect an insurance policy on the artist and prevent him from seeking new management. Though the charges would seem to me mainly for publicity, particularly when considering their age, there have always been questions about Hendrix's untimely demise, ranging from a phantom 911 call to the questions of surgeons who tried to revive the guitarist. Whatever the cicumstances of Hendrix's death, however, one certainty is that exploiting it for profit at this point is ghoulish and a little sad."

PREFIX

DAILY MAG (FULL STORY HERE)

NONEFUCKS

-tony deen

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)